If you’re expecting light-weight, page-turners for the beach, you’ve come to the wrong blogger. For reasons unknown, I like thematic and/or challenging reading over the hot months when I don’t usually have writing deadlines and my colleagues and students are on extended breaks.

A couple of years ago I had an Isherwood summer, rereading Goodbye to Berlin and reading for the first time a couple of volumes of memoirs surrounding that time period in Isherwood’s life. I escaped into that world quite easily, making it one of my more memorable reading summers.

This summer hasn’t followed a theme, but has been a time to catch up with books people have passed on to me and those Kindle books that I picked up on sale and forget that I had them. The summer started with Jonathan Franzen’s hefty novel Purity. This dark comedy is like other Franzen novels, very much a mocking reflection of our times. It interweaves seven overlapping sections of narrative into one story of surveillance culture, social media paranoia and clumsy sex. While I did internally chuckle along the way, I was uneasy at times with his often psychologically weak and yet manipulative female characters.

After that 500+ pager, I needed a novella. Lionel Shriver’s The Standing Chandelier is an excellent study on the psychology of relationships. It stands off a plutonic friendship with a former lover against the relationship that will end up in marriage. While Shriver exercises precision in her word-choice and descriptions, I felt it was in places a bit overwritten, with too much telling analysis, rather than showing and allowing readers to draw the conclusions for themselves. But still a worthwhile and thankfully short read.

Catching-up with my booklist has meant that I’m finally reading Atwood’s The Blind Assassin. I’m not overtaken by the story-within-the-story, and since most of you have probably already read this, you’ll know what I mean. But the main story, set in the early part of  the 20th century in Canada, is exquisitely written and fully engaging.

the 20th century in Canada, is exquisitely written and fully engaging.

I confess that I read a book earlier this summer that for some might be deemed a beach read. Wendy Cope’s collection of prose, Life, Love and the Archers, can be read in bitesize segments, which I guess qualify it for the interrupted reading associated with beaches and sitting out in the garden. Like her poetry, her prose is accessible, thought-provoking and often humorous.

Another beach book of sorts on this season’s eclectic menu is Antoine Compagnon’s collection of vignettes from the 16th century philosopher Montaigne, couched in Compagnon’s historical and biographical commentary. Even the title suggests summertime beach reading – Un été avec Montaigne. That is, summer reading if you’re French. I’m having to look up the occasional modern French word and use context and basic Latin to guess some meanings of archaic terms. Language aside, it’s been interesting to learn that Montaigne was ahead of his time in being an anti-colonialist, drawing attention to the barbarism and oppression Europeans brought to Africa and the Americas. His comments on gender fluidity and hermaphroditism also read as if from a more 21st century liberal-minded time.

So, those are the highlights of the summer book reading, naturally sandwiched between newspapers, online magazines and short stories. Happy reading and stay cool (in every sense of the word).

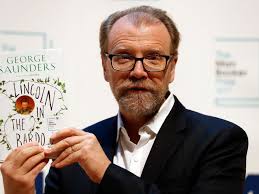

can be found in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Digging up the Bones and closer to the non-fiction end of the scale in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. While Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo hasn’t reached its ambitions, it’s still a better, more innovative, read than much of what’s out there.

can be found in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Digging up the Bones and closer to the non-fiction end of the scale in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. While Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo hasn’t reached its ambitions, it’s still a better, more innovative, read than much of what’s out there.