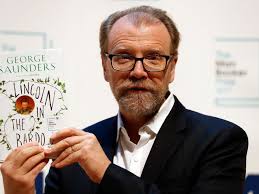

With few exceptions, the Man Booker Prize winner is not as good as half of its shortlist. I’m afraid for me George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo follows this rule. I say this with some hesitation because I’ve enjoyed Saunders’s short stories over the years and because at times the writing in Lincoln is nothing less than brilliant.

Lincoln in the Bardo deals with the true-life story of the death Willie Lincoln, son of the famous president. An exploration of grieving and beliefs about death, it’s set primarily in the bardo – a concept taken from Tibetan Buddhism for an intermediate state between death and rebirth. In this bardo the reader encounters several subplots with a host of fictional (and some fictionalised) characters of which the child Willie Lincoln is one.

Outside of the bardo lies the real world, told through the accounts of present-day historians and journals and memoirs of those living at the time. This genre mixing is a clever way of telling a story. But in order for it to work, the disparate parts, with their different voices and styles, need to be of roughly equal merit. For me, the accounts of Lincoln’s contemporaries were far more moving and interesting than the lives of most of the characters in the bardo. I found myself speed reading through the bardo in order to arrive at and savour the non-fiction passages.

The blending of fiction with non-fiction is an art. True mastery of this art form can be found in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Digging up the Bones and closer to the non-fiction end of the scale in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. While Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo hasn’t reached its ambitions, it’s still a better, more innovative, read than much of what’s out there.

can be found in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Digging up the Bones and closer to the non-fiction end of the scale in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. While Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo hasn’t reached its ambitions, it’s still a better, more innovative, read than much of what’s out there.