Is it a multi-circled Venn diagram or a spider-gram that will best illustrate the connections between Nigel Farage, Steve Bannon, Geert Wilders, Belgium’s racist-right politician Filip Dewinter, current UKIP leader Gerard Batten, Donald Trump and British Nazi Tommy Robinson? It would be too easy to draw circles and lines around the racist and fascist ideas these political figures have come to represent. What also connects these men is far more disturbing. They have all publically endorsed at least two of the names on this list and in doing so have helped to spread each other’s popularity and toxic beliefs. They’ve succeeded in making the hate-filled lone wolves across the West feel and act as members of an international pack.

This wider picture makes a lot of us feel out of control and helpless. Of course, we can always find like-minded people amongst our friends, co-workers and fellow liberal activists. We can choose to read the newspapers and follow on social media those who share our anger and disgust. These things might take the edge off, but it wasn’t until this past Saturday that I found a more satisfying way of confronting this barbarism – by yelling at it.

On a hot Saturday afternoon in Cambridge, a couple thousand protesters gathered to rally and march against another march planned by a group of Tommy Robinson supporters. For my international readers, Robinson is a former leader of the far-right English Defence League who is currently in prison for contempt of court. His supporters, including Steve Bannon, Nigel Farage, Geert Wilders and Gerard Batten, want him released from prison on grounds of freedom of speech. (See what I mean about Venn Diagrams.)

A small group (perhaps 200) of Robinson’s lesser known supporters appeared at the march in Cambridge. We easily out-numbered them – which is intensely empowering. Unlike Trump’s visit to the UK earlier that week, these racists/fascists were within earshot and I felt justified in participating. Will our screamed chants of ‘Nazi scum off our streets’ change the minds of these fascists? Of course, not. Will they think twice before they return to Cambridge for another march? Maybe. Just maybe. And that’s worth holding on to. Aside from the obvious therapeutic effects of yelling at these racist/fascists characters, I’d like to think these groups lose some of their influence and power to directly offend each time they’re pushed away.

There’s also the possibility that I’m all wrong. Our egg-stained door and damaged car could be coincidences and could have nothing to do with Brexit. But in the socio-political climate we live in, an innocent explanation is hard to contemplate. I guess I’ve been writing about The Daily Mail and its political heroes after all.

There’s also the possibility that I’m all wrong. Our egg-stained door and damaged car could be coincidences and could have nothing to do with Brexit. But in the socio-political climate we live in, an innocent explanation is hard to contemplate. I guess I’ve been writing about The Daily Mail and its political heroes after all.

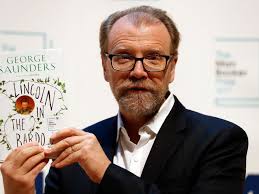

can be found in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Digging up the Bones and closer to the non-fiction end of the scale in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. While Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo hasn’t reached its ambitions, it’s still a better, more innovative, read than much of what’s out there.

can be found in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall and Digging up the Bones and closer to the non-fiction end of the scale in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. While Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo hasn’t reached its ambitions, it’s still a better, more innovative, read than much of what’s out there.

The Fawcett Society’s latest Sex and Power Index is a reminder that outrage and publicity aren’t enough. The study showed that in the UK, women currently make up just 6% of FTSE 100 CEOs, 16.7% of Supreme Court justices, 17.6% of national newspaper editors, 26% of cabinet ministers and 32% of MPs. I’m experiencing déjà vu. A few times a year, figures like this come out, whether from the UK, US or some international organisation. The women’s marches of the last couple of years and the media frenzy over Harvey Weinstein and #metoo seem to have had little impact when it comes to placing women in positions of power. This is made even more appalling by the fact that over the past decade women have surpassed men in numbers entering higher education – that is, we can no longer say that women aren’t qualified for such positions.

The Fawcett Society’s latest Sex and Power Index is a reminder that outrage and publicity aren’t enough. The study showed that in the UK, women currently make up just 6% of FTSE 100 CEOs, 16.7% of Supreme Court justices, 17.6% of national newspaper editors, 26% of cabinet ministers and 32% of MPs. I’m experiencing déjà vu. A few times a year, figures like this come out, whether from the UK, US or some international organisation. The women’s marches of the last couple of years and the media frenzy over Harvey Weinstein and #metoo seem to have had little impact when it comes to placing women in positions of power. This is made even more appalling by the fact that over the past decade women have surpassed men in numbers entering higher education – that is, we can no longer say that women aren’t qualified for such positions.