It’s easy to see how much these two men are alike, down to their speeches made through puckered lips and puffed-up chests. But I’m going to stick my neck out and say how much these two are different. After recently reading Antonio Scuratti’s M: Man of the Century, I look at Mussolini in a different way and as less of a cardboard cutout. This first history-come-novel of a trilogy depicts Mussolini’s early political life from the time of post First World War Italy until he gained power in 1924.

Unlike Tr*mp, Mussolini was not born gagging on a silver spoon. His father was a blacksmith and his mother a schoolteacher. Mussolini trained to be a teacher but worked for a living as the editor of Il Popolo d’Italia, a newspaper for the fasci movement. Mussolini also served in his country’s armed forces during WWI and was wounded. Not so with the former US president, who avoided the draft with student deferments and finally, when those ran out, a medical exemption. Tr*mp’s CV consists of basically one thing – businessperson, a position obtained with properties inherited from his father.

Unlike Tr*mp, Mussolini knew politics and the ways of government. He was active in the Socialist Party before defecting with others to create their own movement over the issue of pacifism during WWI. Mussolini supported workers’ rights while supporting the industrialists, who were trying to reshape and capitalise off the country left bloodied and poor after the war, with little help from their allies America, France and Britain. Tr*mp’s political career was a spin-off from his media personality and self-publicity as a ‘successful’ businessperson.

While both men, once they achieved political power, encouraged and denounced violence in the same breath, Mussolini’s hands were dripping in blood. Metaphorically, of course, since he sent out others to do his dirty work. He specifically ordered the killing of his enemies, including the leader of the socialist party. Some would argue that the orange one is responsible for the deaths on 6 January 2021 at the Capitol, the deaths of anti-racists activists during his term in office and even the deaths of thousands of Americas due to his reckless response as president to the Covid pandemic. But all these examples are about responsibility through verbal coercion and propagandizing.

When it comes to public speaking, while the two men may have presented themselves in similar fashions and to my bewilderment been able to stir up a crowd, the prose of their speeches are starkly different. A skilled writer, Mussolini could craft his language and make logical arguments. And unlike Tr*mp, he never attacked his opponents with schoolchild slurs and name calling, which I’m not going to reprint here as I have reached my saturation point. Mussolini’s discourse would typically pick apart his rivals’ arguments and then tip the rhetorical balance by making threats of violence: “The Socialists ask what is our program? Our program is to smash the heads of the Socialists.”

While both men attacked democracy, it’s worth considering the nuanced differences. Mussolini called democracy a ‘fallacy’ because people do not know what they want and because ‘democracy is talking itself to death.’ Tr*mp said that if he lost the 2020 election, it proved that democracy was an ‘illusion’ because ‘the system is rigged’ and ‘everyone knows it.’

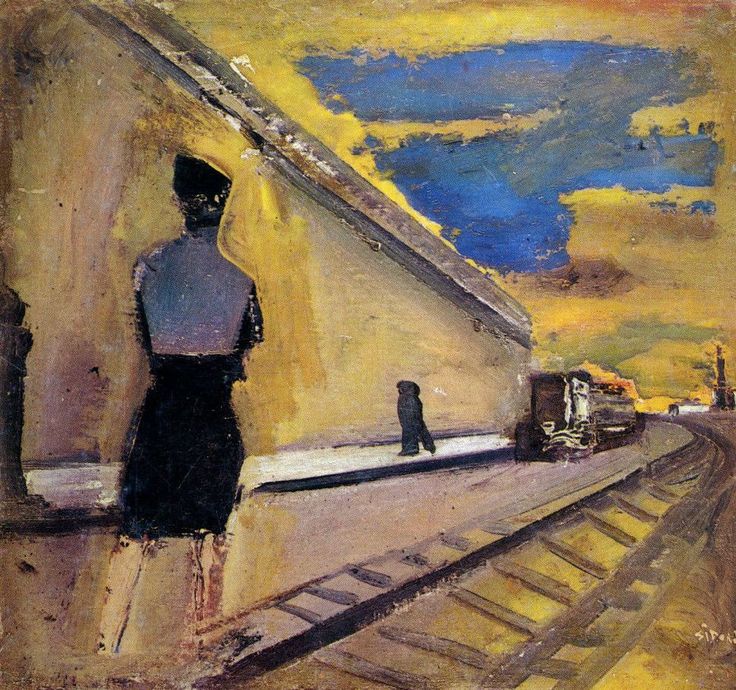

One final noteworthy difference, Mussolini’s fascism, unlike the MAGA campaign, spawned an art movement. Il Novecento rejected the avant garde of the early 20th century in favour of more traditional large landscapes and cityscapes, reflecting the fascists’ ideology. From Scuratti’s book, I’ve learned that this movement was founded in part by one of Mussolini’s many mistresses. Whatever the motivations and manipulations of Il Novecento, Tr*mp and his MAGA movement are in a word artless.

Pointing out the differences between these two leaders not only highlights the unfitness of the former US president for any position of governmental leadership, but it makes me think that fascism is an overused term that like so many political and ideological words, changes its meaning over time. Yet, the essence of it remains as noted in a recent interview with writer Naomi Klein. On the topic of fascism, she said ‘I’m scared whenever we get whipped up in a mob and don’t think for ourselves. That’s how the updated far-right is drawing people in. It’s extremely dangerous.’

What else I’ve been reading

This has turned out to be a summer of big fat reads, with the Antonio Scuratti book weighing it at 750+ small print pages. To counter this, two excellent novellas have capped off the summer. I’ve finally gotten around to reading something by the Belgium writer Amélie Nothomb. Stupeur et Tremblement (avail. in English) is a drole, at times laugh-aloud funny, story of a young Belgium woman’s experience working for a Japanese company. The expected East meets West clashes are there, but so too is a humorous take on workplace bullying (I know, it can be serious and soul-destroying).

The other lightweight but not intellectually so was Thomas Mann’s classic Death in Venice. I first read it decades ago at university. Having since seen the film with Dirk Bogarde, I could only envisage his twinkling brown eyes as those of Aschenbach. The older me also appreciated the references to the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich (who wasn’t on my radar until 5 years ago), adding more meaning to the book’s meditation on aestheticism.