We did consider whether we should go at all. Covid-19 had struck Italy hard, but at that time only the region of Lombardy was in lockdown. Still, northern Italy is just a 45-minute train journey from Nice, and how long would it be before France was in lockdown? Thanks to the European bus service of the sky, Ryan Air, we had rationalised that we could always come back sooner, only losing the money spent on cheap tickets. As we were going to our second home, we didn’t have to worry about the costs of cancelled hotel bookings. Everything would be fine.

We agreed before boarding our flight from Stansted that if anyone was sitting next to us and there were other seats available, we would move, spread ourselves out and play it safe. Sure enough, in our row of three, sitting next to me was a young man with the physical appearance of someone from the Wuhan. David and I moved, guiltily imagining the young man thinking we were paranoid, racists or both. Things were not off to a good start.

As we arrived in Nice, the final weekend of the centuries-old carnaval had been cancelled. Nice didn’t feel like Nice without coach loads of tourists or the buskers and pickpockets taking advantage of the increased trade. Concerts we had planned to attend were cancelled. The city didn’t have its usual buzz of people or vehicle traffic. Fortunately, cafes, restaurants, cinemas and clubs were still open with no talk of closures. Yet, we weren’t going to be foolhardy. We didn’t go to restaurants or our usual jazz clubs and mostly got our croissants at outdoor cafes – if you’re wondering, average daytime temperature was 16C.

While it was important to be cautious, we didn’t want to be sucked into the media hysteria. The information available from British and French health sources made the risks of contracting Corvid-19 appear small. Not wanting to be cooped up in our one-bedroom apartment every evening, we decided to go to the cinema – twice in one week. Before you think we were being foolish, English films with French subtitles (as opposed to dubbing) shown in the early evenings are not typically well-attended. At both films, the dozen or so in the audience spread themselves out while the fragrance of disinfectant hand gel hung in the air.

As the death toll in Italy was skyrocketing, the cases of Covid-19 and deaths were steadily going up in France. This was the unavoidable main topic at my French drop-in class, which I opted to attend because it was at the teacher’s home, usually with only a few students. Again, I was rationalising and trying not to be hypnotised by the wall-to-wall media coverage we were getting in two languages. As it turned out, there were only two students that day, and we both rubbed our hands with disinfectant hand gel at the start of class.

Living close to the Promenade, pleasant seaside strolls and jogs are de rigueur, but we also like our other walks. Problem – getting from our apartment to these picturesque walking paths in Villefranche-sur-mer and Cap Ferrat involves trams and/or buses. In that first week, we braved several tram journeys, keeping a safe distance from people when we could, and two bus trips with near-empty buses. Of course, we realised that others thought crowded buses would be too risky, especially the elderly, who were heeding the advice to stay chez vous.

The week ended with Italy entering total lockdown. We went from slightly concerned to PANIC. My main worry was getting out of France before it would no longer be possible. I had to get back to the UK for meetings and to chair a doctoral exam. My second worry was not being able to get out with David, who was going to stay in Nice for an extra week to paint doors and window frames.

Fear comes in waves. We went from ‘let’s leave Wednesday’ – three days away – to ‘let’s stay here as planned but leave together on my flight in 10 days’ – then back to Wednesday or Friday – or maybe Sunday. Realising that we couldn’t really make up our minds, and that the news about the spread of the virus and the actions of governments were even less predictable than our brains, we held off on booking any new plane tickets. We agreed that whatever we did, we would go back together.

I soon learned from two of my friends back in the UK that people were panicking there as well. Both messaged me to let me know that supermarket shelves had been emptied of toilet roll. I could only chuckle, wondering why food and medicine seemed less essential.

For those last days in Nice, however many they were going to be, we focused on just enjoying the sunshine by day with walks around the city and staying in at night watching Netflix, doing crossword puzzles or me working on a writing assignment. We limited our socialising. We didn’t see our elderly or recently ill friends, but reasoned that it wasn’t unsafe to go to the home of two of our friends who had just arrived from Colorado, which at that point had only recorded two cases of the virus. We greeted our friends with Namaste and at the end of the evening tipsily waved goodbye. Strange not hugging or kissing friends.

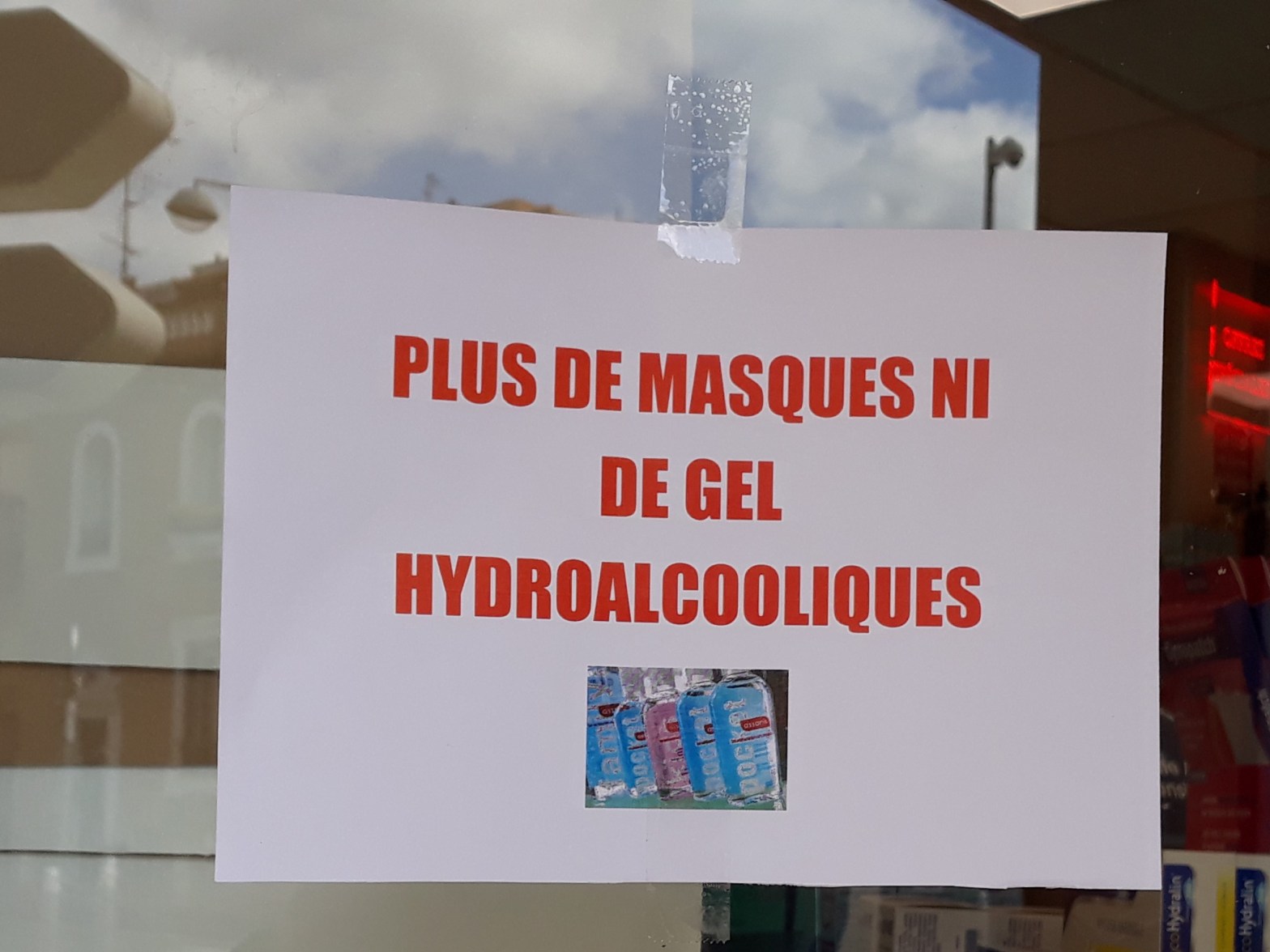

A couple of days later, the death toll in France rose sharply, but mostly to the north of us, while the number of cases in our region doubled overnight. Tr*mp stopped all flights from Europe to America, except for those carrying US citizens returning home. As fewer and fewer people were flying between European countries, airlines were cancelling more and more flights. Ryan Air had still not cancelled our flights, but we knew that we couldn’t stay much longer. Fear was in the air. Half-empty trams echoed with announcements to cover your mouth with a cloth when you sneeze or cough and to keep a social distance – at this point defined as a one-meter space. Disinfectant hand gel and surgical masks had sold out.

The time had come to book a new flight back for both of us. A few days were cut off my working-holiday and 10 days were taken away from David, along with his painting duties.

In the days remaining, I fought off the sense of panic by meeting with girlfriends for an apero in a hotel bar. No hugs, no kisses, but plenty of hand gel and a distance of roughly a meter between us. The following day, I attended my French class – the only student this time. Of course, all we talked about was the virus and people’s strange and sometimes silly behaviours, ranging from Tr*mp’s flippancy to people hoarding toilet paper. I’m one of these people who often uses humour to hide my anxieties – from others as well as myself.

I was indeed anxious. One of us could get ill before our flight, and even though we could manage healthcare in French, it would be easier in English and in a health system that we know. In all of the times I’ve gone to Nice over these past ten years, it was the first time I was looking forward to leaving.

On the day before we flew out schools, universities, restaurants, cafes, bars, non-essential shops and cinemas across France had been ordered to shut. I joked on Facebook about leaving now that the cafes were closed.

As I packed my carry-on bag, I realised I wasn’t taking much back. In fact there was loads of space. Full of embarrassment at myself, I packed two rolls of toilet paper.

At Nice Airport Departures all the shops were closed except for a newsagent. No restaurants or cafes, except for one take-away coffee shop. At the gate, people were keeping a social distance, some of us standing or sitting on the floor in order to have a meter between us. That is until the gate opened and an undignified queue formed – suddenly safe spaces seemed unnecessary. I did wonder if everyone else was as anxious as me to get home.

We’ve been back in the UK for nearly two weeks now, and I still feel as if I’m travelling. I’m a tourist in a country where people only go outside for exercise or to the supermarkets that only allow 25 people in at one time and where customers are ordered to stand 2 meters from each other at the checkout.

Afterward: David’s original flight was cancelled by the airline and he is awaiting his refund. My original flight was also cancelled, but it was later ‘reinstated.’ I was informed of this reinstatement by a text message sent out two hours after my flight landed in Stansted. Like me, Ryan Air makes jokes when they’re nervous.