Regular readers know that I’m not a fan of the listacle – those articles that list the best of or worst of or top 10 etc. They’re click bait and often poor examples of writing. By copping out of the type of commentary or critical review that threads an argument, they offer mere snapshots brimming with clichés. With this hanging over my head for what I shouldn’t do, I’m reviewing 2024 under a few categories.

My year as a verbivore

Yes, I used to refer to myself as a logophile, but I’ve decided to use verbivore instead despite Word underlining it in red. This word was coined by the writer Michael Chabon in 2007 when talking about his love of words.

I’m afraid 2024 hasn’t been good year for verbivores thanks largely to the many national elections taking place all over the world and where politicians have overused words, such as woke, to the point that it can mean the opposite of their original meaning – or simply have no meaning at all aside from being something to despise. I’m also somewhat miffed that words like demure and mindful have gained new meanings thanks to the verbal grasping of social media influencers. Both words are being used to mean low-key and subtle in fashion and style.

The OED ranked brain rot as the word of the year, one that I never used even once. Apparently, it has come out of the Instagram/TikTok generation’s feeling after scrolling through dozens of posts. It can also refer to the low-quality content found on the internet that I do my best to avoid – a challenge when trying to find vegetarian recipes on Pinterest and having to skirt around videos of cats stuck in jars.

While I don’t go around recording myself, I’ll bet that my most used word during this year was incredible. In part, I’ve picked this up from the French who frequently use incroyable. When the worst president in US history (according to historians) gets re-elected after doing and saying so many things that individually should have made him unelectable, that’s incredible. On a more positive note, given my first-hand experience dealing with builders, plumbers and electricians in the South of France, I thought it incredible that Notre Dame Cathedral was renovated after the catastrophic fire in just over five years.

My year as a reader

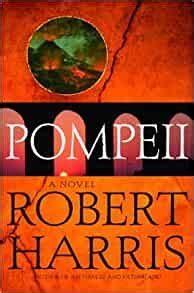

This year has been dominated by two writers as in recent weeks I found myself reading yet another Robert Harris novel, my third this year, and another Amelie Nothomb foray into autofiction, my second for 2024.

After hearing Harris speak about his latest book, Precipice, in Ely a couple of months ago, I delved into this thriller which begins at the onset of WWI. It’s an historical period I’m strangely fond of and the story recounts the true-life affair between Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith and the socialite Venetia Stanley. Asquith’s casualness towards national security is mind-boggling as his teenage-boy infatuation led him to share with Venetia everything from Cabinet debates to classified documents coming from his wartime generals. Though not as complex or informative as Harris’s Pompeii or as intriguing as his Conclave, Precipice is still an entertaining and interesting book.

Taking advantage of the public library in Menton, I’ve just finished Amelie Nothomb’s La Nostalgie Heureuse (avail in English). The narrator’s view on the world is as quirky as ever and expressed with her usual dry wit. In this story, she’s already a well-known writer living in Paris, who returns to Japan to participate in a documentary about her early life. Key to this is an anxiety-provoking reunion with a man she nearly married some twenty years earlier. A noteworthy aside – she (fictional narrator and real-life author) had written about the relationship in one of her earlier books and when the ex-fiancé is asked by the documentary maker how he felt about that book, he said that he enjoyed it as a ‘work of fiction.’ This is when the narrator realises that her truth could be other people’s fiction – a wink to the reader of this autofiction.

Throughout the year, I have also made it a point to read writers that are highly praised in the literary press that I have never read. Earlier in the year it was Paul Auster and Antonio Scurati and in recent weeks Carson McCullers. I finally read The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, which most people know from the 1968 film. Set in a small town in Georgia during the Great Depression, the story recounts the lives of several characters who are connected by their work and family circumstances. Their sense of isolation is explored against a backdrop of poverty and racism, with a nuanced struggle with homosexuality. The weaving of the stories reminded me of a typical Robert Altman film – very enjoyable despite the grim subject matter.

On the non-fiction side, this year I’ve continued my nerdy interests in bees and trees, trying to find texts for non-specialists that aren’t too scientifically dry or too jokingly flippant. While I’ve also read some excellent biographies and memoirs, the most thought-provoking and impassioned nonfiction I’ve experienced this year has been in the opinion pages of the New York Times, The Observer (UK) and Le Monde. They serve as reminders that despite populist voting trends, humanity still exists.

My year as a writer

I started out this year with two writing goals. One was to return to novel #4 and give it a thorough rewrite. While I didn’t produce a full rewrite, I have rewritten about half of it and have made notes for the other half. This task was interrupted by an avalanche of editing assignments that came my way in October and lasted until December. The other writing goal was to simply send out either one short story or one essay every month. I did manage to send out 12 stories/essays this year, but without the monthly regularity – there were a couple of inactive months and a couple bubbling with creativity. Five rejections have been taken on the chin (three were competitions after all) and I await 7 replies.

In the second half of the year, my writing took on a more therapeutic purpose – maybe my way of dealing with complex PTSD. For the first time I’m writing about unpleasant childhood memories and with the creative process taking over, I’m fictionalising certain characters and subplots. I’ve been experimenting with the ‘I-narrator’ by taking on the role of persons other than myself, trying to revisit these episodes from others’ points of view. I seemed to have tapped into something as the work I’ve shown readers so far has been extremely well-received in ways unusual for my early drafts.

My year as a human

Being a linguist, reader and writer are all a part of being a human, but I am aware too that there are other identities of my humanity, such as a friend, spouse, sibling, neighbour, citizen etc. For me, all these roles fill one stratum of physical living in all its sociocultural and psychological dimensions. In this stratum, 2024 has been about witnessing climate change, and then climate change denial by some and inaction by others, along with the public discourse of hate that substantial portions of the population engage with, making me feel like an outlier. I know I’m not alone in this, but I no longer inhabit a space in the norm range.

Another stratum of my humanity exists, but I grapple to explain even to myself. The word spiritual has been stretched and abused by religious and anti-religious alike to the point that I avoid using it. Perhaps this stratum covers all things incorporeal, including abstract thought. This year has made me more aware of this disembodied beingness, if awareness is all I have for now. And so, I continue to practice mindfulness (in the pre-2024 sense of the word – nothing to do with fashionable clothes).

Thank you, readers, for your comments and emoji reactions over the year. I wish you all peace and joy for 2025.