The topic was AI. Today, the topic is always AI. Let’s be honest, whether we see it as a sophisticated search engine, a gushing editor or techno teacher, most of us are using it.

At this online writers’ group, we started by regaling each other with our experiences of dabbling in AI – those silly hallucinations and unnatural conversations where very answer ends in question. Of course, what was said in that meeting ‘stayed in the room.’ With that rule, I braced myself for writers admitting they used AI to help them create and edit their work. But no, a few of us admitted trying it as an editor while others sought its help with research. In my case – I’ll step outside the room – I’ve used it for editing passages of a novel I wrote years ago and was undergoing a major editing/rewriting. I would give Co-Pilot a few pages of a chapter that I felt was sagging and asked it to tighten it up. The Co-Pilot version rearranged some sentences to make them more concise, but in many cases more adjective laden – I’m not a huge fan of adjectives in creative writing. Let the verbs and metaphors do the heavy lifting I say. For me, this teaching tool showed me what I needed to look for in my writing that could be effectively rewritten.

The conversation quickly turned from how we were using it to how it was using us. One author moaned at how Anthropic ‘scraped’ seven of his novels without his permission or financial compensation. He is currently involved in a class-action lawsuit being spearheaded by the Society of Authors. Using a link now available on the SoA website, another novelist discovered one of her books had also been scraped. Outrage mixed with fear – what about the other AI platforms? How do we find out about them? And what about those unscrupulous so-called writers who are using AI – our books – to write formulaic tripe that will sell like hotcakes?

I probably didn’t make myself popular by mentioning that a publisher of one of my academic textbooks contacted me to ask my permission to use my book for training an AI platform. If I opted in, whenever my work is used, it will be referenced with a link to the publisher’s website, and I would receive a small royalty. Of course, I opted in. Really, it wasn’t for the money. My reasoning, which I shared with my fellow writers, is that at least I know my book draws on and refers to peer-reviewed studies, and the final draft of my book was peer-reviewed by two scholars in the field. I was pleased to contribute a reliable source to an LLM. Better this than the grey literature and internet folk linguistics that is being scraped as I write this blog.

No one commented. I was likely to be seen as a traitor.

A few days after the meeting I stumbled across a counterbalance to all this by Wired magazine’s editor, Kevin Kelly. He feels honoured to have his books included in AI training. Kelly says that in the not-too-distant future, ‘authors will be paying AI companies to ensure that their books are included in the education and training of AIs.’ That is, authors will pay for the influence of AI responses that include their works – a type of indirect advertising. Hard to believe this in the current climate.

The one word that didn’t come up at this writers’ meeting, which in hindsight I wish had, is ‘creativity.’ For me, it’s not so much about my published books being so precious. It’s more about the process. The creation and recreation of texts. In the words of Henry Miller ‘Writing is its own reward.’ No bot can take that experience away from me (to paraphrase an old song).

What I’ve been reading

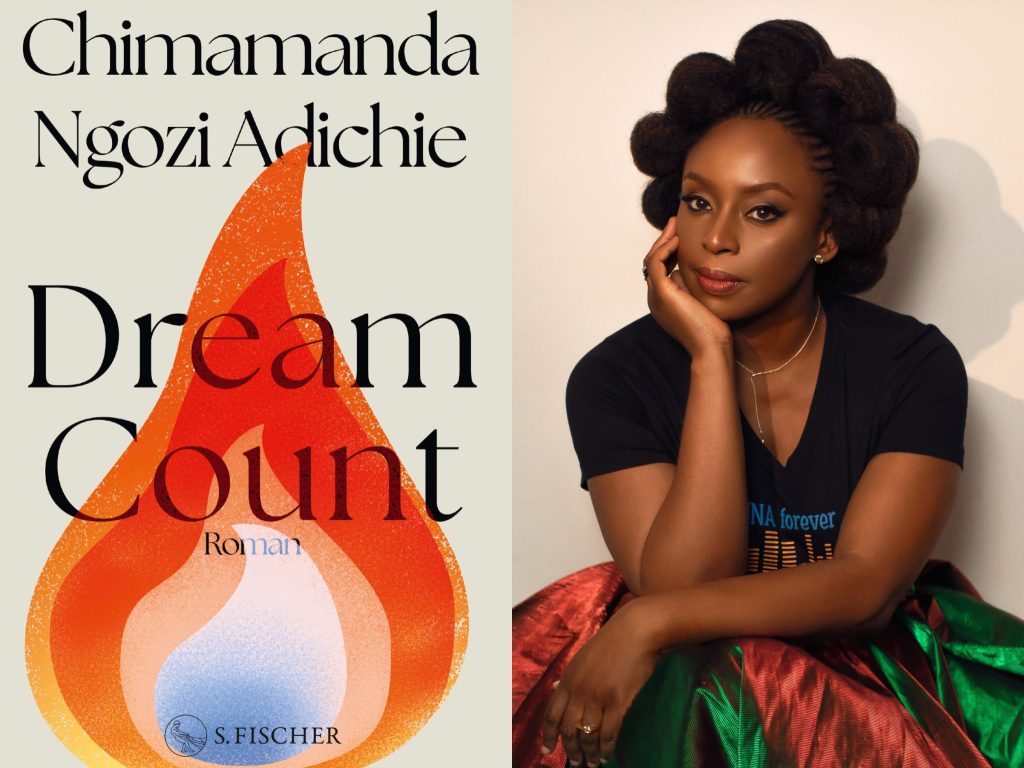

Ocean Vuong is a brilliant writer – an utterly unique voice. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous was his first novel and is written as a letter from a Vietnamese American son to his illiterate mother, knowing she will never read it. Using poetic language and humour, the novel explores themes like identity, trauma and homosexuality. It also conveys a strong social message about the damage done to American families and communities by the opioid crisis. While so much of this novel is philosophically and poetically quotable, I’ll close with this gem:

‘Do you ever wonder if sadness and happiness can be combined, to make a deep purple feeling, not good, not bad, but remarkable simply because you didn’t have to live on one side or the other?’

I can’t imagine a bot producing that, let alone enjoying the act of creating it.