According to Wikipedia, dharma is ‘untranslatable into English.’ Maybe so, as a single word, but the idea of it certainly could be understood across languages, and it’s a useful one for the times we live in.

The term dharma has different meanings across religions. In Hinduism it’s ‘behaviours that are considered to be in accord with the order and custom that makes life and the universal possible. It is the moral law combined with spiritual discipline that guides one’s life. (more Wikipedia – do forgive me). This fits in with its use in the novel La Tress, which I wrote about this summer. In La Tress, a poor woman in India who is an untouchable and works in the public cesspool describes her situation as her dharma. She accepts her job as her place in the world, this ‘order and custom’ that makes everything possible. Of course, there are plenty of social constraints and customs that rule our lives – love them or loathe them – but I struggle to give them moral and spiritual importance. That is, I can see societies using concepts like dharma to keep the poor and women in ‘their place.’

I’m less uncomfortable with the Buddhist’s understanding of dharma. Even though Buddha did not write any doctrines, there are loads of books and websites devoted to the Buddhist understanding of dharma, packed with deconstructions and taxonomies. The most concise workable definition I have found comes from scholar Rupert Gethin, who defines dharma as ‘the basis of things, the underlying nature of things, the way things are; in short it is the truth about things, the truth about the world’ (not Wikipedia, but Tricycle.org). While this might be a bit esoteric, it’s not muddied by debatable concepts such as morality of spirituality.

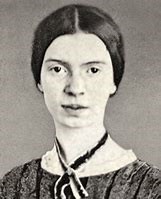

To put this another way still, and although she wasn’t writing about dharma, Emily Dickinson depicted truth as ‘stirless.’

The Truth—is stirless—

Other force—may be presumed to move—

This—then—is best for confidence—

When oldest Cedars swerve—

And Oaks untwist their fists—

And Mountains—feeble—lean—

How excellent a Body, that

Stands without a Bone—

How vigorous a Force

That holds without a Prop—

Truth stays Herself—and every man

That trusts Her—boldly up—

Why am I waxing on about dharma and truth? With the viciously false and conspiracy-riddled election campaigns going on across the world this year, I’m seeking some solace. For now, I’m finding it by embracing the concepts of dharma and truth, allowing me to assume that there are underlying truths in the basis and nature of things. Even if people chose not to believe them, they exist.

What I’ve been reading

Continuing my geeky interest in bees, I picked up Lev Parikian’s Taking Flight: How Animals Learned to Fly and Transformed Life on Earth. As an aside, the secondary title in the US version is: The Evolutionary Story of Life on the Wing. Written for a generalist audience, it’s filled with fun facts about creatures with wings. For example, humming birds (the smallest of all birds), bats (the only mammals that fly) and mayflies that in fact live longer than just a day – most of their lives are spent in the nymph stage, which could last up to two years, and it is the adults that live one or two days. Other flying things get fair coverage, such as pterosaurs, dragonflies and my adorable bees. Unfortunately, the latter is subjected to a lightweight approach full of awe, but a little too low on science for my taste. That aside, highly readable, this book has its place on the grown-up’s shelf as an introduction to one corner of evolutionary zoology.

Robert Harris’s An Officer and a Spy is typical of Harris’s books – historical fiction told in the style of a page-turning spy thriller. The subject this time, the Dreyfus Affair, was already a spy story before it got the Harris treatment. In Harris’s version, the focus is on the French officer Georges Picquart, who worked in military intelligence at the time that Alfred Dreyfus was wrongly convicted for spying and sent to the notorious Devil’s Island. Picquart realises that the case against Dreyfus is flimsy at best. During his investigation, he uncovers the true spy, but when he tries to bring this to light, he too is punished in military fashion. Spoiler alert for readers not familiar with the Dreyfus Affair – eventually the truth wins out. As always, the details and use of real materials and quotes are admirable and what I’ve come to expect from Harris. This brings me back to truths and dharma and at one level what the story is really about. What we think is the truth can change with knowledge and the courage to change the opinions of others and ourselves.

mitations thrusted upon 19th century New England life, especially for women. Although mostly a contemplative and melancholic film, humour and wit are present in a way that I felt was realistic to the poet’s life (Dickinson scholars are free to differ on this point.)

mitations thrusted upon 19th century New England life, especially for women. Although mostly a contemplative and melancholic film, humour and wit are present in a way that I felt was realistic to the poet’s life (Dickinson scholars are free to differ on this point.)