Any kind of revival or revisiting of something from long ago is a set up for disappointment, a total deflation of the nostalgia bubble for sure.

Like so many things in my early life, my entrée into Native American literature came via my determination to be a spiritual person – connected to universal powers, trying to levitate in incense-filled rooms. During my teens, I believed Native Americans were more spiritual than the rest of us. In popular culture, thanks largely to second-rate westerns and new age marketing, these indigenes appeared to have a sixth sense allowing them to see through people and communicate with flora and fauna in mystifying ways. I saw traditional Native American stories with their supernatural elements of talking animals and powerful deities as spiritual as opposed to the mythology and morality tales of the Bible and classical literature.

By my late twenties with my feet more firmly on the ground of literary and linguistic criticism, I was able to straddle Native American fiction as replete with episodes of magical realism. Yet, I privately thought of it as still somehow spiritual. That is, such fiction could be used spiritually, where the magic is mystical, for people in those native cultures and for those of us on a spiritual path – though my path was already becoming marred with potholes of doubt. Indigenous people were still more naturally spiritual in my mind’s eye, but I wouldn’t dare say this to students on my Native American Literature course. I had learned at university some important social skills, including not sounding like a new age hippy in public – such talk is easily mistaken for gullibility. The novels on my course were taught devoid of spirituality and as fictional retellings of reservation life and the treatment of native peoples by the US government with magical realism woven into the stories to reflect the traditional teachings of these peoples.

It was around this time, in the early nineties, that I attended a Native American languages conference in New Mexico, thinking this might be a direction to take my linguistics career. I know this sounds nerdy, but I think I would have done well in language documentation research, recording and transcribing dying languages. This gathering was unlike any linguistics conference I had been to before or since. Talks were introduced with songs and prayers, the latter a strange mix of indigene spiritual teachings and Christianity. As much as I enjoyed the songs and the linguistic research on these heritage languages, I felt disconnected. Two things were at play here. I was one of a few non-Indians in attendance and soon realised that native peoples were also linguists and training others in their tribes in language documentation. I was an interloper. The other point of disconnect came from the very earthy – and I would argue, political – Catholicism out on display. At the time, I was quite uncomfortable around brandishing formal religions of any sort although I was tolerant of spiritual speak and its cousin psychobabble. Suddenly Native Americans were no more or less spiritual than anyone else.

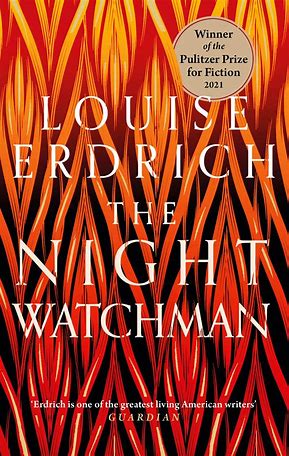

Fast forward 30+ years and several jobs in linguistics later, to where I found myself reading a work of Native American fiction for the first time in decades. Erdrich’s The Night Watchman caught my attention after it won the Pulitzer for literature. I approached this book with a sense of nostalgia, reminiscences of my younger, spirit-seeking, self, gobbling up Indian fictions. Set in America in the 1950s, it’s about an extended family of Chippewas living on a reservation and working under oppressive conditions at a jewel-bearing plant while their tribe’s leaders take on the US government. At the time a bill was going through Congress to end tribal recognition and Indian rights to their ancestors’ lands.

The story has magical realism elements in it – prophetic dreams, a talking dog and an owl that gives signals, but for me they are no longer aspects of spirituality. The story is more socio-political about the way American Indians were oppressed and subjugated to the reservations. I was struck by the language of this passage, referring to the bill proposed in Congress:

‘In the newspapers, the author of the proposal had constructed a cloud of lofty words around this bill—emancipation, freedom, equality, success—that disguised its truth: termination. Termination. Missing only the prefix. The ex.’

More importantly for my older self, this is a story about the treatment of women in 1950s America. The women play the roles of cook, doctor, nurse and maid while coming up against sexual assault and forced prostitution.

While reading The Night Watchman I was reminded of an academic collection of Native American essays and fragments of memoirs, for which I wrote a review in the Journal of Language and Literature. Key to all these writings is the idea of survivance, as opposed to survival. The collection’s editor, Ernest Stromberg explains that ‘While survival conjures up images of stark minimalist clinging to the edge of existence, survivance goes beyond mere survival to acknowledge the dynamic and creative nature of indigenous rhetoric.’ Erdrich’s narrator employs what I would call survivance rhetoric:

‘You cannot feel time grind against you. Time is nothing but everything, not the seconds, minutes, hours, days, years. Yet this substanceless substance, this bending and shaping, this warping, this is the way we understand our world.’

After all these years, I’ve come to realise that survivance is what unites works in the genre of Native American Literature, which includes poetry and memoirs, and this is what is shared between writers and readers. I guess, this realisation is my spiritual experience after all.