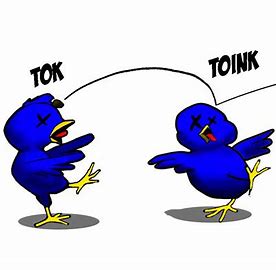

Barbara Ellen hijacked much of my blog this week with her excellent piece in The Sunday Observer about London Mayor Sadiq Khan’s campaign called Say Maaate to a Mate. The core idea is for men and boys to rebuke other male friends for using sexist language and talking about abusive behaviours that could lead to violence against women and girls. As the campaign website explains, ‘We know it’s not easy to be the one to challenge wrongdoing amongst your friends. That’s what say maaate to a mate is all about.’

This type of initiative is just ripe for satire, and I’m sure Ellen and I are not alone in rolling our eyes at it. As Ellen says, which I was going to say, ‘Well intentioned though it clearly is, it all comes across a tad woolly and over-idealised: this idea that, if some guy is making awful remarks, other blokes say “maaate” in a disappointed way and this magically banishes sexism and misogyny from the capital forever. Whaaat?’

Barbara (if I may), allow me to add a couple of points. Firstly, on the campaign website, there’s more guidance on how this airbrush approach to a serious problem works:

‘Mate is a word that needs no introduction. It’s familiar and universal. It can be used as a term of endearment and as a word of warning. This simple word, or a version of it, can be all you need to interrupt when a friend is going too far.’

This reminds me of Nancy Reagan’s anti-drug campaign in the 1980’s. ‘Just Say No’ to drugs was aimed at young people, who duly ignored it. The 1980s witnessed the highest rate of illegal drug use in America in the twentieth century. Like Regan’s ill-targeted campaign, the mayor’s approach to stopping violence against women doesn’t realise how feeble this language sounds in the context of a culture saturated with sexist behaviour and aggressive attitudes towards women. In 80s America, drugs were everywhere, not just on ghetto street corners, but also on public transport, in boardrooms and in bars and restaurants and a fixture of university campuses and high school playgrounds. The same can be said of demeaning and aggressive sexist language spoken to and about women and girls. It operates across class boundaries and can be heard in pubs and sporting events, in offices and classrooms, etc. Worst of all, language targeted against women and girls is pervasive in social media.

This leads me to my second point. Verbal hostility towards women and girls isn’t always so blatant as alcohol-fuelled pub banter or internet trolling. It can be indirect, insipid or give the appearance of even being a compliment. It can be cloaked in humour – and the person who doesn’t find it funny is accused of not understanding the joke. The maaate in these scenarios has plenty of wiggle room.

Barbara Ellen is also on mark when she points out that the funds for this lightweight campaign would have been better spent on policing and resources to help women fleeing domestic violence and for legal support to get convictions against the perpetrators. As that was going to be my closing, I’ll end this rant here and tip my hat to Barbara.