If the name Epstein were not ubiquitous enough, it has seeped into the lexicon as a verb – with two meanings.

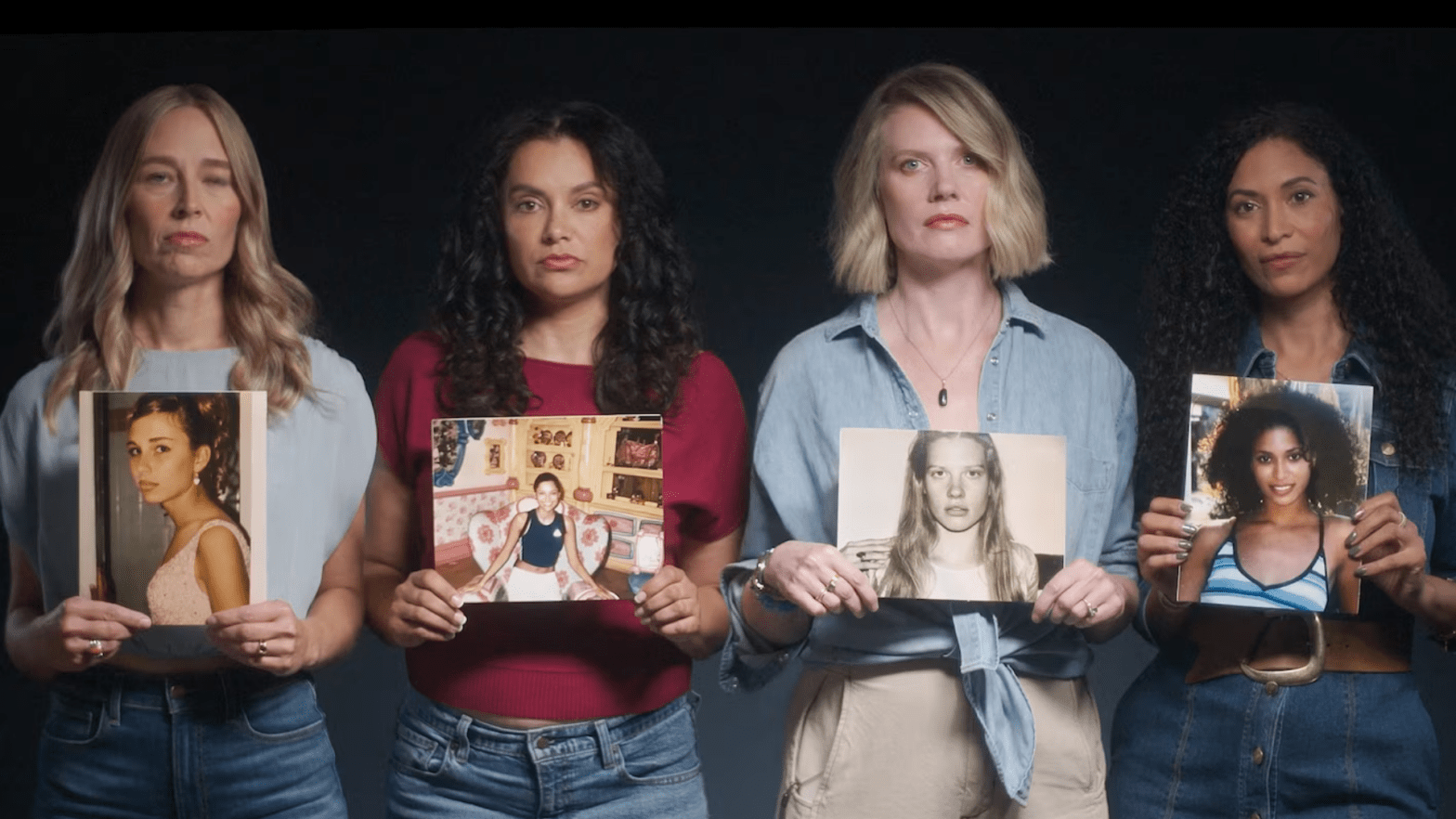

Conspiracy theory websites kicked this off with Epstein (or the lowercase epstein), meaning to make a murder look like a suicide, especially in cases where the motive was to prevent someone from revealing damaging information. While she sits in her cosy prison there’s speculation that Ghislaine Maxwell might ‘get Epsteined.’ This sense has also found its way onto non-conspiracy forums and chats where it’s said in a hyperbolic and jokey way. Example: ‘If he keeps talking about corruption in the agency, they’re going to Epstein him next.’ I take issue with these uses of epstein. Whether serious or jokey, it hinges on Epstein being a victim – even if he was killed, I struggle to see this pedocriminal and master of corruption as a casualty. I’m also bothered by such examples because of their humour – okay, its dark humour, which I often enjoy. But not when it trivialises a case that simmers with rot and where the real victims are mostly girls and young women.

I discovered another meaning of Epstein from reading an article in The Independent by Victoria Richards. She describes how British teenagers have started using Epstein as slang to call out inappropriate or non‑consensual behaviour. Example, when a boy was trying to put something into another’s boy’s trousers, the recipient of the silliness yelled out, ‘Don’t Epstein me!’ Another example from Richards: ‘“Get off, Epsteins!” one of the girls retorted sassily when the rest tried to form a human pile-on of writhing bodies on the sofa.’ At least this sense of the verb epstein is closer to the unsavoury reality of Epstein’s behaviour, not for a second trying to make him out as a victim. Richard’s take on this is poignant: ‘Distasteful, certainly. Yet still, the only way kids can make sense of the very real, human horror they have heard and seen and read about. The only way they can process what adults have done – and in some cases, continue to do – to other young people like them.’

Maybe I’m like those teenagers, trying to process the ‘human horror,’ but I’m using sociolinguistics instead.

What I’ve been reading

Trying to make sense of the political mess we live in, I tucked into Fareed Zakaria’s Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the Present. Like Sunil Amrith’s The Burning Earth, which I wrote about a couple of blogs ago, Zakaria’s book covers hundreds of years of history, but instead of the typical textbook approach, Zakaria argues that the modern world has been shaped by three great revolutions. The first was political – following on from the Enlightenment, the rise of liberal democracies. The second was economic – triggered by the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism (this lessened food scarcity and brought about wealth and leisure time but also inequality and dislocation). The third revolution was (and still is) technological, where we find ourselves today in the digital revolution. According to Zakaria, this is the most destabilizing revolution because it’s outpacing human adaptation. An unsettling thought, yet the book exudes some degree of optimism as it suggests a cyclic nature of these phases of time.

Zakaria, forever the journalist, has a punchy style of writing. Some quotables from the book: ‘Dumping, intellectual property theft, abundant coal, and cheap labour were key ingredients in the growth of US industry in the late-nineteenth century – just as they have been for Chinese industry in the twenty-first century.’ And this one, which fits nicely into my ideological bubble: ‘Even before Trump’s tenure, many people worldwide had stopped regarding the American political system as worth admiring or emulating. America’s present reality combines towering strengths – technological innovation, world-leading universities, strong demographics – with glaring weaknesses, from gun violence to drug overdoses to persistent inequality.’

While reading this revisionist history, my fiction intake came from La pluie d’été (Summer rain) by Marguerite Duras. It’s the story of a poor immigrant family living in the outskirts of Paris in the 1960s. The unemployed parents often leave the children alone for days while they drink and sleep off their hangovers. The children don’t attend school, and this becomes the centre of the action as the eldest son, 11-year-old Ernesto, teaches himself to read and write. With this ability and a sage-like quality, he argues with a local school master who tries to get the children into school. But after 3 days in classes, Ernesto leaves never to return because, as he says, ‘they teach things I don’t know.’ He also questions the social and practical value of formal education in ways that show that he is profoundly wise, a child who seems to carry knowledge that precedes learning. Soon he and his younger sister, Jeanne, develop a bond that is both incestual and symbolically charged.

As the children grow, the novel drifts between realism and myth. Ernesto becomes a kind of visionary figure, speaking in riddles about destruction, creation, and the future. Ultimately, La pluie d’été is less about plot – it’s a meditation on knowledge, innocence, family, and the fragile, luminous moments that shape a life. The writing is a mix of traditional novel storytelling with some of the dialogue – those on education and the existence of God – presented in the format of a stage or screenplay. At the end of the novel, this is explained by the acknowledgement to an early film version of the work. Retaining parts of this as a filmic dialogue is quite effective and keeps the work pacey. Also in this acknowledgement is a thank you to the culture minister at the time of writing, Jack Lang. Yes, the same Jack Lang, now aged eighty-four, who’s embroiled in the Epstein scandal as his name appears over six hundred times in the notorious files alongside some dodgy financial dealings. Perhaps someday epstein the verb will also mean ‘to be exposed for criminality despite being protected by your wealth and power.’