My pause from blogland can be attributed to one thing – moving and settling in Menton. If you’ve been following this blog for a while, you’ll know that David and I have had a second home in Nice for nearly 15 years. We sold that and most of the furniture in it back in September and waited five months for the deal to close on our new apartment in Menton, up the coast from Nice. We’re still in the same neck of the beaches, the Cote d’Azur, famous for its year-round sunshine, clement winters and history of artistic and celebrity residents.

Recreating a home in the south of France has involved an embarrassing amount of shopping – from a flatpack bed to drill bits, with a second-hand sofa, dining table, chairs and curtains along the way – and intensive decorating, featuring the massacre of butterfly and floral decals and the removal of in-built wardrobe and cabinets, leaving behind the tasks of scraping off wallpaper and filling vacant screw holes marks with buckets of Polyfilla, soon to be followed by painting. Luckily, no major renovations are needed. We have a tastefully tiled bathroom with walk-in shower and a fully functioning kitchen, albeit with a temperamental washing machine that prefers to work in the mornings.

My bloggery silence hasn’t been just about furnishing and DIY in extremis. This move marks the start of my retirement in earnest, the deletion of the prefix semi before retirement to describe my academic position. I’ll finish my last contract with my final doctoral student in the autumn. That’s all that’s left. My life is now devoid of course writing and research and the publish or perish culture. That is strange – as strange as a local bus trip to Italy, as strange as swimming in the winter sea. Like so many retired people, I’ll continue to ‘keep a hand in’ as they say, taking on the odd editing assignment that comes my way. The difference now is that for the first time in my adult life, I’m not looking for work or trying to keep the work I’ve got.

This naturally makes me think about my other career as a writer. I haven’t considered myself semi-retired from that. I used to think that writers never retire, but some writers have packed it in (Phillip Roth and Wendy Cope come to mind). I’m starting to wonder if I should take at least a partial retirement from writing. This means working to my own pace on fiction and creative non-fiction and still calling myself a writer (it’s too sexy to shake off). This isn’t too different from what I have been doing in recent years, since I stopped scriptwriting and therefore applying for funding, managing a theatre group and delivering workshops. Yet something different is palpable, my ambition, my desire for writer recognition, ended around the time we put in our offer on the Menton apartment.

I can’t stop all together – writing is as natural as breathing and as necessary as meditation. And there still are things to write about – nature, personal growth, language, books…

What I’ve Been Reading

A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara makes for a long book (700 plus pages) but is also one of the best novels I’ve read in decades. It tackles difficult subjects, like abuse, torture and self-harm, and this can make for painful reading at times. But there are payoffs. The psychological depths of the story, revolving around the friendships of four men over the years and one man in particular, Jude, presents a complex and believable narration. Jude is a perpetual victim, but also a survivor that other characters (and this reader) agonise over and applaud in equal measure.

The Authority Gap byMary Ann Sieghart,written a few years ago, covers the myriad of ways in which men are assumed to have more authority, more knowledge and experience than their female counterparts. By the author’s own admission, you would have thought that this has all been said before and that we have moved on to a more equal co-existence. Yet, it’s something that we know still happens and have become desensitised to and have stopped talking about. Or in my case, being all too aware of this, occasionally I have used my bone-dry sense of humour to point out that I’m the Supervisor and not a mature student or that yes, I really did this [fill in the blank with something technical] all by myself without causing grievous injury. Seighart points out how the authority gap is played out in our actions, individual and institutional, and in our use of language. Specific examples come from a hefty dataset of anecdotes from powerful women, including some of my heroes like Christine Lagarde, Julia Gillard and Madeleine Albright, who have all been undermined and underestimated. Amusing and cringeworthy at the same time.

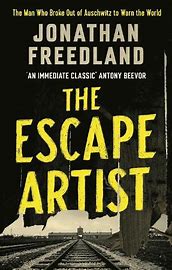

Seven Days to Tell You by Ruby Soames is a remarkable thriller, full of twists that go beyond the plot-driven variety, questioning the ideas of love and commitment. Since I don’t want to give anything away – discovery and speculation are key to reader enjoyment – I’ll have to be brief. A woman’s husband disappears for three years. To say more than that would even spoil the curious first chapter. I will say this – it takes place mostly in London, but also has flashbacks to the French Riviera, hence, I conclude this blog from where it began.