You would be forgiven if you assumed that this blog is about intrepid war reporters donning padded vests and helmets. Instead, I’m looking at another type of journalist. The marking of World Press Freedom Day last month brought to my attention the targeting and suppression of environmental journalists.

UNESCO reports that since 2010 at least 44 journalists investigating environmental issues were killed, with only five resulting in convictions. UNESCO also observed the growing number of journalists and news outlets reporting on environmental issues that have been the victims of targeted violence, online harassment, detention and legal attacks. Just looking at Afghanistan, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, since 2004 more environmental journalists have been killed there than those who died covering the country’s military conflicts.

To no surprise the top issue that makes journalists targets is climate change. The power of the fossil fuel industries and their links to governments are certainly one of the driving forces behind these attacks. So too – and equally worrying – is the growing polemic around this issue that makes ordinary people, often hiding behind the anonymity of online platforms, hostile to environmental activists and journalists.

I dabbled in environmental journalism but felt a bit of a fraud because I don’t hold a degree in life sciences or environmental studies. Even though my articles were more political than scientific, I never thought I was doing anything courageous or risky by writing them. Yet, I wouldn’t want to be caught out underestimating the power of those who disagree with my views or prefer the public to be ignorant of the evidence, scientific or experienced. These days I’ve taken up the safer option of nature writing with its indirect pleas to polluters.

The importance of protecting environmental journalism is summed up on the UNESCO website:

‘The climate and biodiversity crisis are not only affecting the environment and ecosystems but also the lives of billions of people around the world. Their stories of upheaval and loss deserve to be known and shared. They are not always pretty to watch. They can even be disturbing. But it’s only by knowing that action is possible. Exposing the crisis is the first step to solving it.’

What I’ve been reading

John Boyne’s The House of Special Purpose is an enjoyable read, though lacking the depth and irony of his The Boy in the Stripe Pyjamas. The story is set in Russia at the time of the revolution and in London over the years that follow until the late twentieth century. It is I’m afraid another fictional account of the massacre of the Romanov’s and the fate of Princess Anatasia, who many believe escaped unharmed and lived under an alias for the rest of her live. Given the horrible deaths of the Romanovs, the colourful character of Rasputin and the intrigue over Anatasia, this is a story that keeps on giving. In Boyne’s version, the human story is in the foreground and makes this a worthy read even if the Romanov saga is starting to wear.

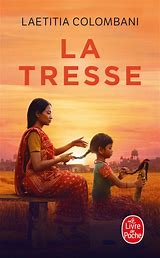

La Tresse (The Braid) by Laetitia Colombani was recommended to me by one of my French language partners. It’s a thin middlebrow book that has been enormously popular in France and now all over the world in translation. It recounts the lives of three women who, as you can guess, like the strands of a braid overlap into a single unit. How this narrative braid is formed is what keeps the pages turning. Each of the three women struggles against the hand they’ve been dealt. Smita is an untouchable in India, where she cleans the village latrines and endeavours at all costs for a different life for her daughter. Giulia lives in Italy and works at her father’s wig factory. Her troubles arise when her father falls into a coma, leaving young Giulia to discover that the family is on the verge of bankruptcy and could lose their home and factory. The third woman, Sarah, is a high-profile lawyer and single mother in Canada who is struck down by illness and the ruthlessness of her colleagues too eager to capitalise from it. These weighty topics are recounted in prose interspersed with poetry, language brimming with metaphors and motifs that gently creep up on the reader.

My non-fiction reading these days has been monopolised by newspaper and magazine commentaries on the verdict against a former US president, now a felon, who is prohibited from entering the UK to play golf on his own Scottish golf course. Reminding readers of the horrors of the Tr*mp years – including his attacks on the press – and what this verdict might yield in the not-too-distant future, worth reading are David Remnick in the New Yorker and Simon Tisdall in The Observer. Of course, both are expressing views I share.