With all the news coverage of the situation in Israel, I hadn’t planned to read any books on the topic any time soon. When taking in such horrible and complex news, I tend to mix reportage with commentary, newsprint with television and podcasts, trying to make sense of it and to distinguish between factoids and misinformation. All the while, I’m too aware that the unfolding humanitarian crisis is being presented in ways intended to tug on heartstrings and stir up anger. I thought I was getting close to my news saturation point with this war.

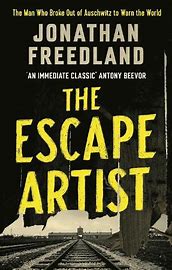

But then, I realised that two books I happen to be reading these days are related to this conflict. Both books draw from personal accounts of well-known and documented events of the twentieth century. One is The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World by Jonathan Freedland, a non-fiction book I mentioned earlier this year, having first heard the author talk about it in an interview. The other book, Le Pays des Autres (The Country of Others), is Leila Slimani’s reimagining of the lives of her French grandmother, Mathilde, and Moroccan grandfather, Amine, who settled in his native Morocco post-WWII during the fight for independence from France.

These stories overlap during the Second World War, presented in Slimani’s book in flashbacks of Amine fighting for the French colonisers when he met and fell in love with Mathilde. The Middle East as we know it today was geopolitically constructed by western powers of the past two centuries through force and exploitation. In the aftermath of WWII, Muslim cultures revolting against the West and their allies reverberated across North African to the eastern Mediterranean. As Slimani taps into this resentment and deep-seated hatred of the French in post-war Morocco, it’s hard to not make parallels with the contemporaneous creation of the state of Israel and the consequences of years of deadly conflicts.

The first half of The Escape Artist is set in Auschwitz during the war while the mass murder of Jews was taking place and follows the story of Walter, a Slovakian Jew, who was deported to a labour camp at the age of 18 and miraculously escaped two years later with a fellow Slovakian prisoner. These escapees kept mental records and described what they witnessed in forensic detail to Jewish leaders in Slovakia. The second half of the book recounts the difficulties in getting governments across the world to act on this Auschwitz Report before thousands more were killed, and the story continues with Walter’s troubled personal and political life after the war. Such events related to the war have been referred to throughout this most recent war in Israel.

Both books present the complexities of ethic bias and hatred, highlighting the sense of otherness with an awareness of inexplicable contradictions. Even though Amine has married a French woman and appears to harbour a secret esteem for the French, he becomes violent with rage when he learns that his sister is having a relationship with a Frenchman. By taking the narrative to the years following Walter’s escape, Freedland’s book covers the stories of Jewish leaders who collaborated with the Nazis to save their own families and who after the war – with nothing to personally gain – became character witnesses for Nazis that were put on trial. When the current Israeli conflict is looked back on, I suspect we’ll find similar sentiments and anomalies.

While I hadn’t intended on reading any more about the Gaza conflict beyond the daily news reports and their commentaries, it seems I have. This makes me even more aware of colonialism and the Second World War being as much about the present as they are about the past.