‘As we resist Trump and his regime, we weaken it. As we weaken Trump and his regime, we have less to fear and more reason for hope. As we have less to fear and more reason for hope, we are able to vanquish tyranny and build a better future.’ This is according to Robert Reich, commenting on the No Kings demonstrations in America. I get what he’s saying, and I agree in theory—but honestly, sometimes these ideas just end up as pub talk or dinner table debates, never really going anywhere.

Part of the problem lies in the word resistance and its verb form to resist. The word resistance first appeared in English in the 1300s meaning “moral or political opposition” and referred to violent uprisings against European feudalism. Later in the same century resistance denoted “armed opposition by force” (Online Etymology Dictionary).

Fast forward a few centuries, and scientists started using it in the 18th century to talk about opposing the flow of energy. No weapons needed. The phrase path of least resistance came along in 1825, taking on an even softer figurative meaning – it’s an expression I’ve heard myself use to describe dealing with colleagues and difficult family. In the present day, we resist temptation to eat another cheese-encrusted tortilla chip or purchase something we really don’t need but want badly.

So, resistance can feel empowering and even rewarding. But there’s a flip side. I heard it in a ‘Morning Calm’ meditation on the Samsung Health app—the soothing voice talked about resisting change and trying to control things you just can’t. Sometimes, resistance just makes you miserable.

While I was writing this, I received another newsletter from Robert Reich, insisting ‘The resistance is becoming an uprising. Last Saturday, more than 7 million of us poured into the streets to reject Trump’s dictatorship. That’s more than 2 percent of the adult population of the United States. Historical studies suggest that 3.5 percent of a population engaged in sustained nonviolent resistance can topple even the most brutal dictatorships — such as Chile under Pinochet and Serbia under Milosevic.’

That’s all well and good, Robert, but Pinochet hung on to power for 17 years and only left because a new Chilean constitution stopped him from running again. Milosevic was taken down by international courts for war crimes. I don’t see America getting a new constitution anytime soon—and even if it did, Trump would probably just ignore it or twist it to suit himself. The international community seems to either flatter him or go their own way without America and without attacking the president’s tender ego. There’s no big global push to hold him accountable for human rights abuses (like what ICE is doing in the US or military attacks on civilians off Venezuela and Colombia).

Nonviolent resistance is great. It brings like-minded people together, pushes the media to question the government’s narrative, and most importantly, it gives us hope. But resistance alone isn’t enough. If all we do is resist – especially when change feels like an endless uphill climb – we risk burning out, disillusioned and miserable.

I’m reminded of the opening to a poem by Maria Melendez Kelson:

The Indiscriminate Citizenry of Earth

are out to arrest my sense of being a misfit.

“Open up!” they bellow,

hands quiet before my door

that’s only wind and juniper needles, anyway.

You can’t do it, I squeak from inside.

You can’t make me feel at home here

in this time of siege for me and mine, mi raza.

Legalized suspicion of my legitimacy

is now a permanent resident in my gut.

(from ICE Agents Storm My Porch)

What I’ve been reading

Jennie Godfrey’s The List of Suspicious Things served its purpose as a non-gory and non-violent bedtime read – I’ve learned not to read Joyce Carol Oates if I’m horizontal with pillows under my head. Though not predictable, Godfrey’s novel wasn’t challenging or as engaging as I had hoped it would be. The premise is intriguing. Set in 1979 in Yorkshire at the time of the Yorkshire Ripper murders, a young girl sets out to find the notorious murderer by observing the people in her neighbourhood, assuming it must be one of them. Her suspects are only suspicious because of the ways adults treat them, exposing the racism and prejudice of the society at the time. The story follows the coming-of-age genre with her realising these ways of the world and the limited tolerance of adults.

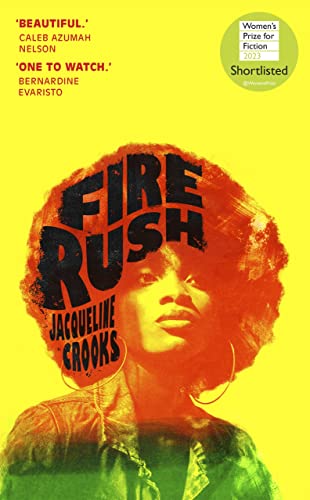

I found a meatier and more interesting read in Jacqueline Crooks’s Fire Rush. Also set in the 1970s, but in the vibrant Afro-Caribbean community in London. It’s earthy and real, where the language lifts off the page and the characters smoke weed and spend their evenings dancing at an underground club. The story turns into one of resistance against racism and police brutality. Despite the injustices and the violence, I was left with a satisfying sense of community, reminding me of Zadie Smith’s White Teeth and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah.

Finally, going back into the archives of my mind, I reread The Stranger by Albert Camus. I had only recalled from my undergraduate days that this was a story of a French Algerian loner. Forgive my younger self. Of course, the novel is much more than that. With a new film adaptation out in France, the book’s getting fresh attention. In a recent interview, novelist Lilia Hassaine said The Stranger could be called Soleil amer—bitter sun. The main character, Meursault, doesn’t deny his guilt or resist his fate. He finds comfort in the sun, even in his cell. Hassaine rightly describes the sun in the novel as both beautiful and bitter.