Have you ever wondered if speaking a different language could change the way you perceive the world? It’s a fascinating question that has captivated linguists and researchers for decades. While many have assumed that our thoughts and feelings are by and large universal, emerging research suggests that the language we speak can significantly influence the way we see the world, creating differences for speakers of different languages.

The idea that language can shape our perception of the world is not a new one. It’s often associated with the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which claims that the structure and vocabulary of a language can determine or at least influence the way its speakers think and perceive reality. The Sapir-Whorf examples using Native American languages have been discredited over the years. Yet, growing evidence supports the idea that language can indeed mould our thoughts and experiences.

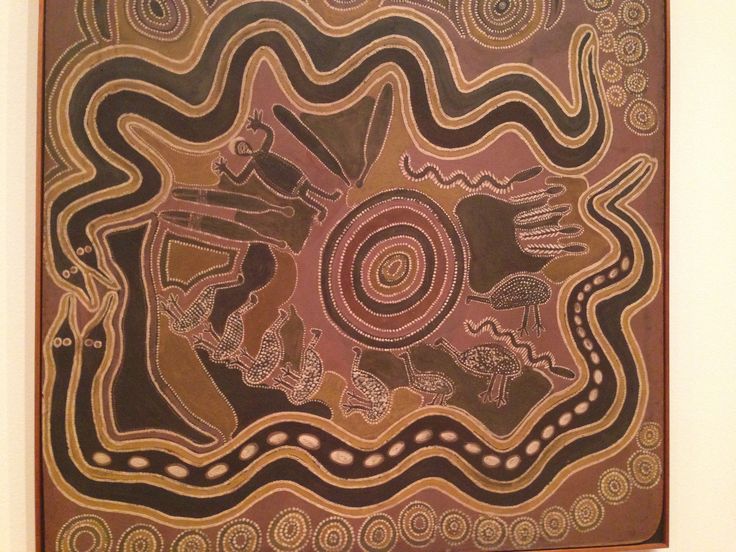

One of the most intriguing studies exploring the relationship between language and perception comes from research conducted on the Aboriginal language of Murrinhpatha in Australia, reported in the current issue of Scientific American. Murrinhpatha has free word order, where subjects, verbs and objects can occur in any position in a sentence. In the study, Murrinhpatha and English speakers were shown the same image of a woman. Monitoring the eye movements of the participants revealed that English speakers focused first on the woman, then on what she was doing (perhaps looking at her hands) and finally on other features in the background. This reflects the tendency in English to have the subject first in the sentence followed by the verb and then adverbial phrases that describe the circumstance or background. Murrinhpatha speakers had faster eye movements that darted around the images, often taking in the background features first and then the foreground and back and forth again. The linguists involved suggest this could be the result of free word order.

While it doesn’t prove that language completely determines thought, it suggests that different languages can indeed shape the way their speakers experience the world around them.

This article also mentions something that has been troubling me for a while. So much of linguistics research and the resulting textbooks have come from scholars of the English language and to a lesser extend from similar Romance and Germanic languages. Most of the work that has followed in Chomsky’s footsteps in their obsession for universal properties of language and language processing has been based on a group that represents less than 5 percent of the total number of world languages. As the psycholinguist Evan Kidd put it, ‘The search for universals took place in only one corner of the language universe.’

As I write this, I’m working on an editing job for a Chinese post-graduate student who is trying to apply Chomskian principles and their descendants to Chinese grammar. While the student (and I as an editor) struggle with this assignment, I often wonder how different this would be if Chinese scholars developed generative grammars first before Chomsky.

Back to the beautiful diversity of language, Scientific American has this to say about the work conducted by the recent study: ‘…each language represents a unique expression of the human experience and contains irreplaceable knowledge about the planet and people, holding within it the traces of thousands of speakers past. Each language also presents an opportunity to explore the dynamic interplay between a speaker’s mind and the structures of language.’

To listen to Murrinhpatha, check this out.