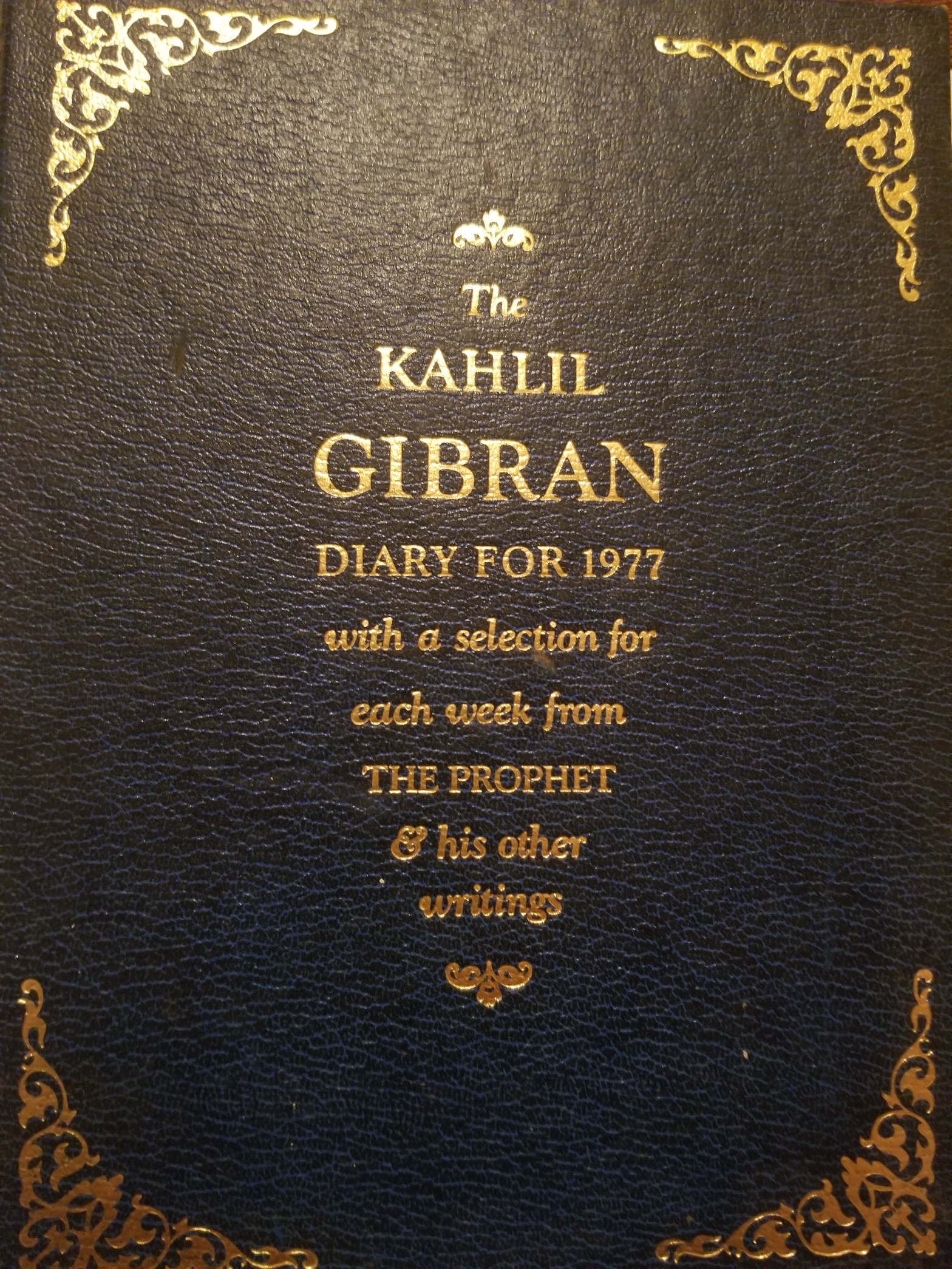

In 1977, Kahlil Gibran was cool. The artist, poet and philosopher was well-suited to 60s and 70s America. Best known as the author of The Prophet, Gibran’s words appeared on posters of serene landscapes, sunrises and out-of-focus lovers. Some posters included his drawings, reminiscent of William Blake, also popular at the time. Quoting Gibran was in fashion for the lecture circuit of peddlers of consciousness – creative consciousness, spiritual consciousness, universal conscious – everything was consciousness. This was the background that Christmastime of 1976, when my teenage self purchased the 1977 Kahlil Gibran Diary. Every other page had a quote from the famous poet alongside a blank page for me to write in daily. I’ve held onto this Gibran Diary all these years though I would call it a journal these days. It’s been stored in various locations in America, shipped across the Atlantic and stowed away and moved to various locations across Britain. Many pages are yellowed and it holds a slightly dusty mildew odour.

Today, living in what I suppose is the last third of my life, I’ve started re-examining the first two-thirds and mining my early journals for writing material. Opening this 1977 book for the first time since I was writing in it, I was hit in the face by my naïve teenage musings – obsessed with sex and death – and dreams of a grown-up life. Worse still, I came up against my own poor writing. I mean this in two senses of the word writing. My penmanship was painful to read with letters crunched together for most words with others stretched out as if taking a breather from my nervous hand. While my school report cards shined with top marks, the teacher’s comments inevitably included something about my illegible handwriting. For the other sense of writing, I was creative and could devise little narratives with quirky characters, using humour and descriptive imagery, but hopeless with the mechanics of writing. I wrote as I spoke in fragmented sentences – or their painful cousin, the run on sentence with a string of dependent clauses. I pretentiously employed erudite terms, often hitting the wrong tone or leaving my reader bemused. It’s easy to say this and analyse it now, but I do feel some mortification on behalf of my younger self.

Mediated by the journal, this conversation with teen me has brought back those formative years, the role of new age spirituality in a life riddled with family dysfunction. I wonder to what extent I was a product of that time period in American social history. Many political and social aspects of the mid 1970s escaped my notice then, being preoccupied with family and school life and most frighteningly with what was happening to my body. The Kahlil Gibran quotes, by the way, may have been read, but I rarely commented on them or used them to inspire my own writing. I’ve realised that if I’m to convert these writings into an essay, I can’t trust the limited memories or understandings of a teenager. Adding a political and sociocultural context to my young life gives me a chance to share my adult knowledge and build on it at the same time. What is the point of a writing project that I can’t learn anything from?

Okay, I’ve written about it – now if I can only get back to writing it.